- Home

- Grant Faulkner

Pep Talks for Writers Page 11

Pep Talks for Writers Read online

Page 11

The town should be nice, but not full of diversions. You don’t want to be tempted to be a tourist.

A big goal is crucial: Without a goal, it’s too easy to settle for writing less. The purpose is EXTREME WRITING.

Make sure you’re well equipped in all matters, whether it’s books you need for research, notebooks, or favorite writing foods.

Make sure you’re well rested to start. Extreme writ ing takes the kind of energy and endurance a challenging sporting activity does. You can’t muscle your way through 12 hours of writing a day if you start at a deficit.

It’s important to get support from your partner if you have one, and maybe even your friends and family. You want a clear head, not a guilty or distracted head.

My life only allows for one or two such writing retreats each year at best, but it’s an amazing feeling to move a creative project forward not in dribs and drabs, but with speed and force and resolution.

Which gives me an idea . . . if I can’t get away for a mini writing retreat, maybe a mini-mini retreat is in order—a single day of extreme writing. Go!

TRY THIS

POWER WRITE

Short-term goal: make a plan to spend an entire day writing in the next month. Long-term goal: make a plan to write for an entire weekend sometime in the next year. Write long. Write hard.

34

SLEEP, SLEEPLESSNESS, AND CREATIVITY

You wouldn’t think sleep would be a topic in a book about creativity. We all do it. We’ve done it for years. We have to do it. It’s biological. What’s the big deal?

Yet the annals of literary history are littered with writers madly typing through the night, suffering tortures inflicted by insomniac demons, or conjuring a story during sleep itself. Mary Shelley saw Dr. Frankenstein hunched over his creation in a fevered reverie one night. Virginia Woolf wrote the end of her novel The Years after “the sudden rush of two wakeful nights.” Marcel Proust penned much of In Search of Lost Time while staying awake all night due to a chronic illness.

As a long-term insomniac, I’ve thought nearly as much about sleep and sleeplessness as I have about writing. Sleep abandoned me like a cold-hearted lover when I was in my early 20s, and it became a distant object of yearning and frustration. I didn’t know what I’d done to merit such betrayal. My insomnia was a torment, a horror—an “eternal quivering on the edge of an abyss,” as F. Scott Fitzgerald described it. There are few things quite so damning as hearing the clock strike three o’clock, four o’clock, and five o’clock, knowing that the time for any restful replenishment has passed. I desperately needed sleep for my body, my soul, my brain, but when I shut my eyes, my hoped-for dreamland gave way to my overly excited, overly anxious, overly imaginative state.

After several years, though, I began to accept my sleeplessness, and I even viewed it as a blessing. When I stopped wrestling with it, it became less nocturnal anguish, and more of a waking dreamland—“an oasis in which those who have to think or suffer darkly take refuge,” as Colette wrote. There are few things sweeter for the imagination than quiet solitude in the deep darkness of the night. Unlike time during the day, when I’m awake at night, it’s my time. I feel like I’m the only one who’s awake in the entire world, and I blessedly get this bonus solitary time that others don’t to look inward and reflect. I know it sounds a bit perverse, but one must turn a lemon into lemonade when possible.

That said, I don’t think insomnia or the fevered waking dreams that writers have had should be romanticized in any way—because sleep is a powerful force of good for creativity. The quality of our sleep influences our mood throughout the day, shapes the way our mind moves around thoughts and experiences, and provides the energy for our imagination to truly take flight. We live in a culture shaped around a 24-hour cycle, though, a world that paradoxically produces more and more high-octane energy beverages in tandem with an ever-expanding arsenal of sleeping remedies. Too many view sleep as something that can be put off, or they wear their sleeplessness as a badge of honor to show off their work ethic, but sleep should be revered for its magical possibilities. Writers need an intensity of emotion, a heightened vitality, to do their best work, so we should worship at the altar of sleep and do whatever we can to sink into those strange hours of the night.

The reason sleep is one of the best things for creativity, ranking even ahead of exercise, is that our brain turns into a mystical land during sleep. Sleep helps consolidate memory, builds remote associations, and integrates all sorts of disparate thoughts, experiences, and emotions that our daytime rational minds see as separate and unrelated. That’s why the advice to “sleep on it” is true. Sleep creates connections between things that didn’t seem connected before. It’s essentially a creativity machine, a contraption designed by Rube Goldberg that connects dissimilar ideas, images, and memories in a way that appears to make sense. A good night of sound sleep is actually an invitation to the muse to come in and play.

That’s why the first liminal moments after waking, when you’re drifting in that hazy, hallucinatory terrain between sleep and waking, are a hallowed time of creativity when many an ah ha! moment occurs. Consciousness hasn’t quite taken over complete control and we can gently daydream our way to a new thought.

Sleep is a bit like food in our many different proclivities, tastes, and needs. Sleep is something to explore creatively, to notice how your mind works at different times of the day and night. Think about what type of creator you are after different qualities of sleep. View sleep (and even sometimes sleeplessness, at least in my case) as your creative companion. Instead of fighting it or trying to outwit it, indulge in it, luxuriate in it, and absorb its otherworldly powers.

TRY THIS

DREAM YOUR STORY

Some believe you can hack your brain during sleep—train it to serve you creatively. Write down a story problem and put it next to your bed. Review the problem for a few minutes before going to bed. Tell yourself you want to dream about the problem as you drift off to sleep. On awaking, lie quietly before getting out of bed. Do you recall any traces of your dreams? Write them down—right away, before you lose them.

35

BE DELUDED . . . BE GRAND

The phrase delusions of grandeur generally carries a negative connotation. It connotes one who’s out of touch with reality. One who is arrogant. One who expects the royal treatment.

It can be all those things, but I want to put a twist on such notions. I posit that a writer needs to seize delusions of grandeur when they strike, to even nurture those delusions and view them as the rare and precious gems they are.

After all, much of one’s writing life is spent in the opposite frame of mind, right? After suffering through states of crippling self-doubt, if not self-damnation, shouldn’t we be granted a moment of reprieve to dream that the novel we’re writing will capture Oprah’s eye, win a National Book Award, and be made into a movie by Martin Scorsese (with a cameo role for the author, of course). Oh, and then there’s Elton John’s Oscars party, where a Vanity Fair photographer will snap a photo with Jennifer Lawrence, George Clooney, and the usually overlooked author—you!

Many a great actor has been inspired by an imaginary future Oscar speech, conjured on a dreary bus ride to an everyday job. Most of those actors don’t get the Oscar, so you can call them deluded, but where would they be without the hope?

The life of an artist is filled mainly with rejection. I think being a writer is like being a baseball player: if you have a .300 batting average, you’re a really good hitter, but most of the time you don’t get on base.

After a day of head-banging synaptic sclerosis at our writing desks, it’s too easy to muck around in the gloomy thoughts that we’re not good writers—that maybe we shouldn’t have even embarked on this crazy endeavor. As T. S. Eliot once said, “When all is said and done the writer may realize that he has wasted his youth and wrecked his health for nothing.”

Such reckonings can only be balanced by the opposite: our h

opes and dreams. Great creations are spawned by many things, but appropriate doses of fanciful reveries are sometimes underrated when compared to the lauded artistic battering rams of diligence and self-criticism. Great creations are fueled by our dreams. Our dreams, as crazy and seemingly delusional as they might be, are the best antidote to self-doubt; in fact, they’re a slickly paved pathway to vigorous and daring creativity. “Confidence is 10 percent hard work and 90 percent delusion,” said Tina Fey.

If you’ve had a tough day of writing, I recommend taking a shower and rehearsing what you’ll say to Oprah. Toast your present and future self with the humble, generous remarks you’ll make when your kick-ass, awe-inspiring novel sweeps the world away.

TRY THIS

GET READY FOR THE RED CARPET

Write a short acceptance speech for your ultimate writing award. Envision success. Let your mind be carried by these dreams when you’re in the shower, washing dishes, or walking your dog.

36

NURTURING AWE THROUGH DARKNESS, SOLITUDE, AND SILENCE

I once met a man who told me he didn’t dream at night. I’d never heard of such a thing, so I wondered how that could be possible. We are such mysterious, unfathomable creatures, with a never-ending well of thoughts, images, and stories that rise in wild somnambulant juxtapositions during the night. It’s as if thousands of Salvador Dalis dash about in our minds and sprinkle faerie dust in our synapses. To live a life without dreaming is almost like forgetting how to laugh.

The only explanation I could think of is that this dreamless man had let his subconscious become so trammeled by his day-to-day work that he’d smothered the songs of those ornery, wise, fey sprites of his interior life. I sympathized with this man. I, too, in the heat of a busy life sometimes feel as if I’ve lost access to the mysteries that reside within me. To lose one’s dreams is a symptom of a frightful disregard for the critical stirrings within, where our inner voices register the sacred, precious moments of awe—an awe that rings with the vibrant pulses of life, an awe that sows our stories with resplendency and grace.

We need to feel awe to sense a world larger than the banalities that fill too much of our days. To feel awe in such a pure and transformative way, we don’t need to visit the seven wonders of the world; we simply need to heed the wondrous workings of our interior life and make time for the practices that nourish and develop it. In order to create, an artist must first receive—to practice an invocation of mystery. I try to remind myself how the capacity for awe is present in my life every day, literally at my fingertips, and one way to trace its reverberations is to observe and revere things that our modern life too often covers up: darkness, solitude, and silence.

We need darkness, silence, and solitude to recognize the opaque flickerings of our unconscious.

Can you imagine a day without electric lights, a day where you live by just natural light? Instead of reading by the mysterious flickers of candlelight and going to bed according to the natural rhythms of the day’s light, we now control light. Instead of letting ourselves be gently cloaked with darkness as the sun sets, welcoming the silver slivers of the moon, our eyes stare at the light of a TV, mobile device, or computer, to the point that the darkness of the night goes largely unrecognized. The darkness of the outer world opens up the interior world. All of those malnourished nocturnal sprites slink out from under their rocks and realize it’s time to play. The ashes of old memories flicker and catch fire. Darkness enchants with its incantations, the reveries it draws forth. We just have to pause to cloak ourselves in it, receive what it invokes, and our stories will be the richer for it. “If you want to catch a little fish, you can stay in the shallow water. But if you want to catch the big fish, you’ve got to go deeper,” said the filmmaker David Lynch. Darkness invites us to go deeper.

Likewise with silence. Have we ever lived in a noisier era? We can play nearly any song in the history of the world and watch nearly any movie. Cars clutter the highways. Dishwashing machines, heaters, air-conditioning—even when we try to inhabit the silence of our homes, noises roam and mingle. People define silence nowadays as putting in their earbuds—shutting out the world with other noises, not breathing in the quiet peace of stillness. In order to make art, we must find the space, the quiet, to become intimate with our own minds.

Thomas Merton, the poet and Trappist monk, said that people need silence in their lives to “enable the deep inner voice of their own true self to be heard at least occasionally.” When that voice isn’t heard, he says, we’re essentially exiled from our home, with the noises of our lives the equivalent of a locked door, blocking us from the shelter of our lives within. Silence is not just an absence of sound, but an awareness of an inner stillness that attunes the mind’s ear to what would otherwise remain hidden.

When we encounter absolute silence, it’s almost shock-ing—to suddenly hear the sounds of our breaths as if the world inhales and exhales with us. Silence is an ablution, a cleansing of one’s thoughts, an invitation for your inner life to walk about and perhaps even dance. Sit with silence, let it be, enshrine yourself in it, and if you listen closely, the world within you suddenly becomes a chorus, and the words of a story are born.

Darkness and silence both become heightened with solitude. Solitude defined not as an evening alone binge-watching the latest hit show online, but as a reflective, meditative, interior exploration. We might be lonely, but we’re rarely truly alone. When we’re in the midst of people, we give away pieces of ourselves. We react to others, stepping in and out of the personas of ourselves. We become other things, tentacles sprawling out in many different directions, making it difficult to notice the world’s mysteries.

But genuine solitude is a sort of dream time. Your inner voice suddenly becomes audible, and you’re wonderfully more responsive to yourself. Time is unburdened, and the maelstrom of the world diminishes. The question of what it means to be alive moves to the forefront, and you’re more attuned to neglected stories, neglected thoughts. “Be quite alone, and feel the living cosmos softly rocking,” said D. H. Lawrence.

We need darkness, silence, and solitude to recognize the opaque flickerings of our unconscious and follow the images that rouse, puzzle, and feed us. We need to magnify our spirit through awe, and then bring that sense of awe to our words.

TRY THIS

AMPLIFY YOUR SPIRIT

When was the last time you experienced an extended period of solitude? What was the last night sky you sat under? Dedicate an hour one night to sitting alone in the dark. Go outside if you can and sit under the stars. Pledge to reserve time each week to attune yourself to the awe that resides within you.

37

NEW EXPERIENCES = NEW THOUGHTS

Travel memories form their own strange dream. Somehow the sun always shines at a different angle in another country. The air holds a different weight, a different texture, and the everyday becomes effervescent. A simple cup of coffee in a train station in a different city can become an experience you might remember forever.

There’s a reason some of our most creative moments occur when we travel. The visceral thrill of being someplace new, stepping out of our life, following the drift of our thoughts, and experiencing new people, sights, and food stimulates new connections, new ideas.

We are creatures of movement. I suppose we’re a migratory species because at one time we had to roam in search of food or to find a better climate, but we also travel out of pure curiosity, a primal need to discover something new and different (or just for the sake of a peripatetic panacea to mundanity). We’re highly sensitive to new sounds, sights, tastes, touches, and smells, so synapses crackle and spark in all sorts of directions when we travel. That’s why that cup of coffee in a train station becomes memorable. It’s not a mundane cup of coffee. It’s a cup of coffee in Buenos Aires, Barcelona, or Boise.

Our routines, our everyday experiences, put blinders on us. When we think about things in our everyday lives, our thoughts are bound geographic

ally and cognitively. We’re less likely to conjure or chase a remote tangent because our thoughts are shackled by the familiar. But when we travel, we’re able to see something new in the old. We escape from our little ecosystem and move beyond the armature of our habits, inviting in obscure notions, errant ideas, and brazen new concoctions in surprising ways. Instead of connecting A to B as your brain normally might do, it connects A to C, and then C to H, and then H to A, which leaps to X. Or something like that. We might not have known we were suppressing such things, which is why travel is so important. Travel makes us feel alive in ways that most activities don’t.

But the creative benefits of travel aren’t just about weaving a vast quilt of different experiences. Travel is a cognitive training ground for creativity. Travel trains your mind to be open-minded, to notice differences. When we travel and experience the way people in other cultures behave, we’re more likely to see life through varied lenses. A single thing can have multiple meanings. Travelers tend to be more sensitive to ambiguity, more able to realize that the world can be interpreted in varied ways that are all equally valid. The ability to engage with people from different backgrounds, to get out of your own social comfort zone, helps you to build a rich, acculturated sense of self. Travel is “fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness,” as Mark Twain wrote in Innocents Abroad.

There’s a rich heritage of authors who created some of their best work when living in different places. Haruki Murakami said that living in the United States infused the feeling of alienation in his novel The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. Isabel Allende’s classic magical realist novel The House of Spirits started out as a series of letters that she wrote while in exile in Venezuela to her dying grandfather in Chile. In The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams, the peregrinations of Arthur Dent were influenced by Adams’s use of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Europe on his youthful travels.

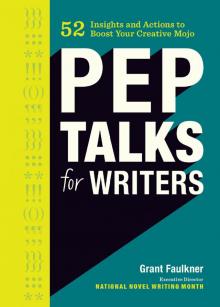

Pep Talks for Writers

Pep Talks for Writers